Long before the Mayflower landed at Plymouth Rock in 1620, attorney advertising in Britain was frowned upon by both barristers and the courts. Incitement of vexatious litigation and financing litigation without an interest in it were punishable, not by statute, but by an antiquated custom of professional disgust and shunning that could go all the way up to the bench.

In short, the rationale behind the prohibition of lawyer advertising was that it operated to diminish the integrity of the profession.

The Card and Shingle.

When America was colonized by the British, the laws of England came with them. The general rules were that attorneys were permitted to negotiate their own fees on a case by case basis, and acceptable advertising consisted of a shingle and a business card. No other types of lawyer advertising were permitted.

On rare occasions, those business cards began sprouting up in local newspapers, but that was about as far as attorney advertising went for about 250 years. Even when an attorney advertisement would be published, it was the content of the advertisement that was taken exception to and not the fact that it was an attorney’s advertisement. Just about all lawyers continued to follow the professional gentleman’s agreement not to engage in advertising their services.

Bates vs. State Bar of Arizona:

As the United States evolved, various state codes of professional conduct were implemented in the 20th century, but there was general agreement on the prohibition of lawyer advertising and the solicitation of legal services. Pursuant to American Bar Association (ABA) guidelines, advertising continued to be restricted to business cards, some of which might indicate a lawyer’s name, address, phone number and areas of practice.

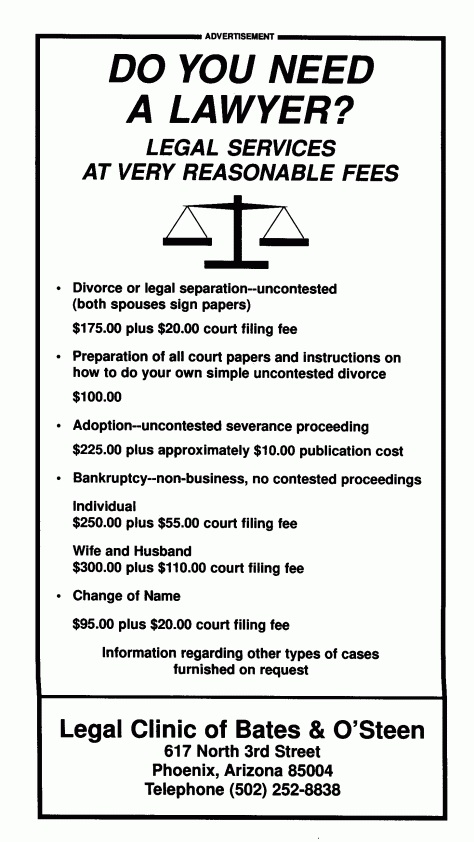

Then, on February 22, 1976, Arizona attorneys John Bates and Van O’Steen placed an advertisement in the Arizona Republic that notified readers of certain routine legal services that they would perform at specific prices. It was labeled as an advertisement, and it provided appropriate information on how to contact the two attorneys at their law firm’s office. At the time of publication, Arizona prohibited attorneys from advertising.

An ethics complaint was brought against Bates and O’Steen, and the state’s disciplinary commission recommended a minimum of a six-month suspension from the practice of law for each of them.

Penetrating the Market.

Bates and O’Steen appealed the decision to the Arizona Supreme Court, and the recommended suspensions were reduced to censures. The commission’s ruling on prohibited advertising stood though, so Bates and O’Steen asked that the U.S. Supreme Court hear their case. It granted their request, heard the appeal, and on June 27, 1977, it ruled that Arizona’s prohibition of lawyer advertising violated First Amendment commercial free speech guarantees. The court reasoned that since bankers and engineers are allowed to advertise, young lawyers should be able to advertise too. Otherwise, a prohibition against advertising would operate to “perpetuate the market position of established attorneys.” Much to the chagrin of those established attorneys, the court’s opinion went on to hold that advertising should be allowed “so as to aid the new competitor in penetrating the market.”

Lawyers, Accountants, Plumbers and the Yellow Pages:

For many lawyers in the United States, 1977 was a lifetime ago, but to date, a significant percentage of lawyers continue to object to lawyer advertising, even if it’s done by the letter of the law. As newspaper ads were now permitted by the Bates decision, those ads were placed with other print media too.

Remember the Yellow Pages? You probably don’t even have a current phone book in your home, but there was a day when if a person was in need of legal services and didn’t know a lawyer, he or she would begin their search in the Yellow Pages, much like finding an accountant for taxes or a plumber for a leak.

Then, there were the television commercials during the afternoons or late at night. Were those slots used because air time was cheaper, or injured or nearly bankrupt people were at home, without work and awake? Some law firm television ads were beyond successful, while others bordered on being distasteful. Then, there was that guy in scuba gear who did a commercial underwater.

Now it’s the Internet.

As opposed to the era before the Bates decision, the ABA is now encouraging law firm advertising.

Online law firm advertising has overshadowed law firm television advertising. It has also proved to be the most effective form of legal services advertising. The return on investment is substantial, and it’s considerably less expensive than print or television advertising.

An internet presence also makes it easier for attorneys to be found by potential clients who don’t have a phone book anymore and don’t watch daytime or nighttime television. How successful are law firm websites? As per the National Law Review, 74% of all potential clients visit a law firm’s website prior to taking action.

During the COVID-19 era, legal website content readership has skyrocketed, as has reading time on specific pieces of content. Legal website users appear to have established a sense of trust with certain lawyers and law firms. Those lawyers and law firms have also developed a reputation for credibility. With that interaction, readers are likely to become clients sometime in the future for whatever reason.

The Rules After Bates.

With the Bates decision, lawyer advertising is here to stay. Although the ABA has established legal advertising guidelines, they’re advisory in nature and not binding. Since the Bates decision, the individual states have put their own regulations in place that govern such advertising. A legal advertisement might be a gauche and distasteful communication, but given First Amendment commercial speech considerations, the general rule is that it is likely to be permissible, so long as it isn’t false, misleading or doesn’t make material misstatements.

As per the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision stated in Bates, “Advertising does not provide a complete foundation on which to select an attorney. But it seems peculiar to deny the consumer, on the ground that the information is incomplete, at least some of the relevant information needed to reach an informed decision.” There is a generation of lawyers out there that couldn’t imagine not being allowed to advertise their availability. Others believe that any advertising other than a business card and sign at a law office should be prohibited. Maybe well-established law firms don’t like the competition for clients. More than 40 years later, Bates remains debated.